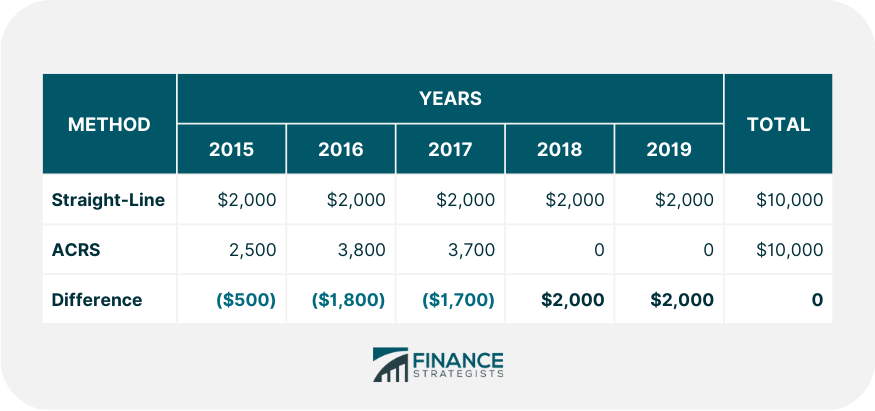

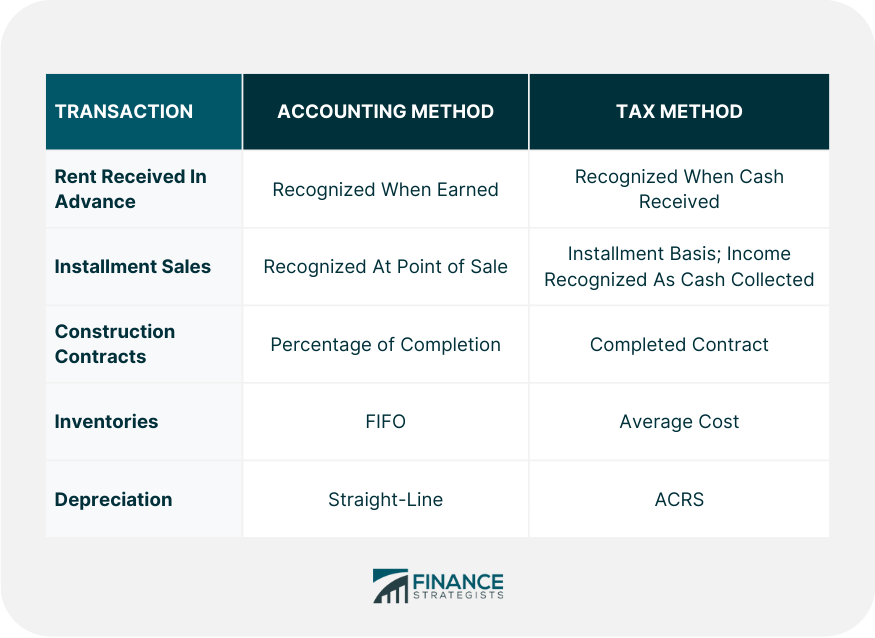

Differences exist between the generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) and the provisions of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC). These differences arise due to the varying objectives of GAAP and the IRC. The objectives of GAAP are aimed at providing investors and other users of financial statements with reliable and relevant financial information. The objectives of the tax law contained in the IRC include social equity, ease of administration, political considerations, and ensuring that individuals and corporations are taxed when they have the ability to pay. Furthermore, there are many cases when the management of a firm will use one accounting method, such as straight-line depreciation, for accounting purposes and another method, such as ACRS-based depreciation, for tax purposes. Therefore, prudent management will often select those accounting methods by the IRC that will minimize the firm’s taxable income and, thus, reduce its cash outflow due to taxes. On the other hand, the same management may select a different set of accounting principles for financial reporting purposes. Differences between accounting income and taxable income can be classified into permanent and timing differences. Permanent differences enter into the determination of accounting income but never into the determination of taxable income. They are, in effect, statutory differences between GAAP and the IRC. An example of a permanent difference is interest on state and local bonds. Although interest on these items represents revenue from an accounting perspective, it is not included in taxable income in either the year received or the year earned. In the US, Congress did this in order to make it easier for states and local governments to raise revenues by making the interest on their obligations nontaxable. Since these differences are indeed permanent, we are not concerned with them. Timing differences are the other reason that accounting income in any year may differ from taxable income. Timing differences result from the fact that some transactions affect taxable income in a different period from when they affect pre-tax accounting income. However, over the life of a particular transaction, the amount of income or expense for accounting and tax purposes is the same; it is just that it is different within the various periods. An example of a timing difference is the use of straight-line depreciation based on the asset’s economic life for financial reporting purposes and the use of ACRS depreciation for tax purposes. Generally, in the first few years of the asset’s life, ACRS depreciation exceeds straight-line depreciation, and pre-tax accounting income is reduced to less than taxable income as a result of depreciation. However, in later years, the timing difference reverses. Straight-line depreciation now exceeds ACRS depreciation, causing a greater reduction in accounting income than in taxable income as a result of differences in depreciation. To illustrate, suppose that a company purchases a light truck at the beginning of 2019 for $10,000 and decides to use straight-line depreciation for accounting purposes, with a 5-year life and no salvage value. The firm takes an entire year’s depreciation in the first year, meaning that annual depreciation is $2,000, or $10,000 + 5 years. For tax purposes, the asset has a 3-year class life, and under ACRS the depreciation percentages are 25% in the first year, 38% in the second year, and 37% in the third year. The following table compares the annual and total depreciation under each method: In the first three years, ACRS depreciation exceeds straight-line depreciation, but in the last two years, straight-line depreciation exceeds ACRS depreciation, which is reduced to zero. There are several other timing differences between taxable income and accounting income. Some of the more important ones are summarized in the below example. You should remember two points. Timing differences affect two or more periods: the period in which the timing difference originates and the later periods when it turns around or reverses. However, over the life of a single transaction, the amount of accounting and taxable income or expense related to that transaction will be the same. It is just a question of when timing differences affect accounting and taxable income.Sources of Differences Between Accounting and Taxable Income

Permanent Differences

Timing Differences

Example

As the table shows, over the life of the asset—in both cases—the total depreciation is $10,000.

Differences Between Accounting and Taxable Income FAQs

Taxable income is the amount of money that an individual or entity must pay taxes on while accounting income is the net operating profit after all expenses, including taxes, have been accounted for.

Common deductions from taxable income include charitable donations, mortgage interest, state and local taxes, health insurance premiums, alimony payments and certain business expenses.

Depreciation affects accounting and taxable incomes differently; it reduces a company's tax liability by allowing them to deduct depreciation costs from their taxable income but does not reduce their accounting income.

Taxable income includes all sources of revenue whereas net income only includes primary sources of revenue, such as wages or interest earned on investments. Additionally, deductions that can be made from taxable income do not necessarily apply to net income.

Itemized deductions may be used for either accounting or taxable incomes, depending on the type of deduction it is and how the organization treats it for tax purposes. Generally, most expenses listed in an organization's books will qualify for a deduction but may not be applicable to the taxable income figure if they are not listed separately on the tax return.

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide, a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University, where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon, Nasdaq and Forbes.